Not long ago, when the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was still new, another controversial piece of European legislation caused an internet uproar.

Article 13 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market implied a potential ban on memes — and people had a lot to say about it.

Of course, we now know the EU did not ban memes.

But join me in this expose where we look back fondly on the moment in history when Article 13 (and its controversial sister provision, Article 11) caused a lot of fear regarding the future of good old-fashioned fun on the Internet.

What Is Article 13?

Article 13 was part of a draft of a European copyright directive and required platforms that host user-generated content to have measures in place to prevent their users from violating copyright laws, sparking controversy.

It was introduced to the public in the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (Copyright Directive), a comprehensive copyright and licensing directive that sets overarching standards for the European Union (EU).

Article 13 was one of 24 provisions outlined in the Copyright Directive, and it specifically addressed the role of platforms and online sharing service providers like:

- YouTube

- Google News

Article 13’s original phrasing required all user-posted content featuring copyrighted material to have express permission to be on that particular platform:

“An online content sharing service provider shall therefore obtain an authorisation from the rightholders […], for instance by concluding a licensing agreement, in order to communicate or make available to the public works or other subject matter…”

Helen Smith, the executive chair of the Independent Music Companies Association (IMPALA) at the time, was quoted by Music Business Worldwide saying, “This will be the first piece of legislation anywhere in the world clarifying the position of platforms as regards copyright and licensing.”

People interpreted this to mean it would ban the sharing of any copyrighted images, giving it the contentious nickname ‘EU meme ban.’

Was Article 13 Actually a Meme Ban?

No, Article 13, which became Article 17 in the final version of the directive, did not end up banning internet memes.

In fact, Part 7 of Article 17 of the in-force Directive exempts user-generated content that is:

- Quotation, criticism, review

- Use for caricature, parody, or pastiche

So, internet memes are here to stay.

Why Did People Worry Article 13 Would Ban Memes?

Draft Article 13 caused controversy because its initial phrasing implied that the responsibility for ensuring copyright compliance fell on the service and not the content creators.

People worried that silly images with funny captions, like the one of the Nickelodeon cartoon character Spongebob Squarepants, pictured below, would be taken down by every platform.

Critics expressed concerns over how platforms could reasonably obtain licensing agreements from every content owner, especially when users regularly posted and shared:

- Pictures

- Videos

- Clips

- Sound bites

- Songs

Mass monitoring of that scale necessitates automation, likely in the form of upload filters.

Cory Doctorow of BoingBoing made an astute comparison at the time, saying, “This is Internet As Cable Television: Millions of sites and services collapsed down to hundreds, each a mere distribution arm for media companies, with the public relegated to “viewer” status, unable even to communicate with one another.”

But due to the edits to the final Copyright Directive, such worries subsided and no mass monitoring needed to be implemented.

What Is Article 11, aka the “Link Tax”?

Article 13 wasn’t the only provision of the Copyright Directive sparking controversy — people also expressed concerns over draft Article 11, referred to as the “link tax.”

It initially required platforms to obtain licenses before publishing works from other news outlets, and the fee that aggregate sites would have needed to pay individual publishers earned it the name “link tax.”

The original draft of Article 11 described only the following exemption:

“…shall not apply in respect of uses of individual words or very short extracts of a press publication.”

The exemption clause was notably vague, as it did not clarify or define what “short extracts” meant.

Many people interpreted it to mean that snippets and images from a news story are still subject to the link tax, including big names like Google.

In fact, Google conducted a study to test how this could impact aggregate news platforms and independent publishers and found a 45% drop in traffic to the publishing news outlets.

But in the final version of the directive, Article 11 turned into Article 15, and now clearly states:

“The protection granted under the first subparagraph shall not apply to acts of hyperlinking.”

The updates to Article 11 of the Copyright Directive stopped the “link tax” from occurring.

Why Does Article 13 Matter?

After the passing of the ePrivacy Regulation and the GDPR, the Copyright Directive was another piece of legislation coming out of the EU aimed at shaping the Internet — and it wasn’t the last.

We’ve since seen the EU AI Act and the Digital Markets Act impact the Web and beyond.

Most of us remember that the GDPR wasn’t without some controversy when it came into effect in May of 2018.

However, unlike the contention surrounding Article 13, the GDPR was generally viewed as a positive step in an ongoing effort to protect the privacy of internet users.

Along with the ePrivacy Directive, people saw both as attempts to protect the public rather than corporate interests.

The public responses to the potential meme ban and other provisions of the Copyright Directive draft were far more negative than the reactions to the two data protection laws.

Many people felt that Article 13 wouldn’t protect individuals but instead might silence them, unlike the GDPR and ePrivacy Regulation.

How Did People Respond to a Potential Banning of Memes?

Let’s examine how people responded to Article 13 before the draft was revised.

Those in Favor

Some people were in favor of Article 13.

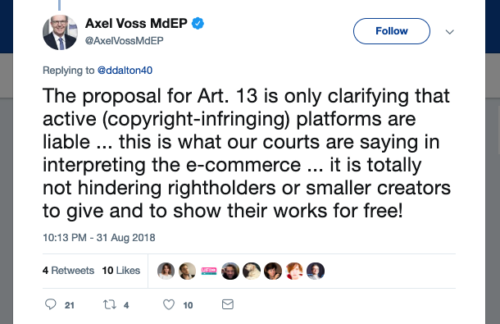

One of the most active voices was Parliament member Axel Voss, who often took to X (called Twitter at the time) to defend the Directive, with such tweets as the one pictured below.

Outside the political sphere, some musicians also voiced support for the Directive, like James Blunt, who uploaded a video expressing why he advocates for Article 13.

Blunt says, “I’ve been so lucky to be able to make music, but the next generation of artists coming through needs to get a better deal when their music is used online.”

He adds, “I believe we need a world where the effort and creativity that goes into making music is rewarded fairly.”

Along with Blunt, fellow artists like David Guetta signed a petition launched back in 2016 in favor of the Copyright Directive.

While there was support for Article 13, the voices in opposition were far more prevalent.

Those Opposed

In 2019, nearly 5 million individuals signed a petition to stop draft Article 13, started by saveyourinternet.eu, and became one of the largest petitions in EU history.

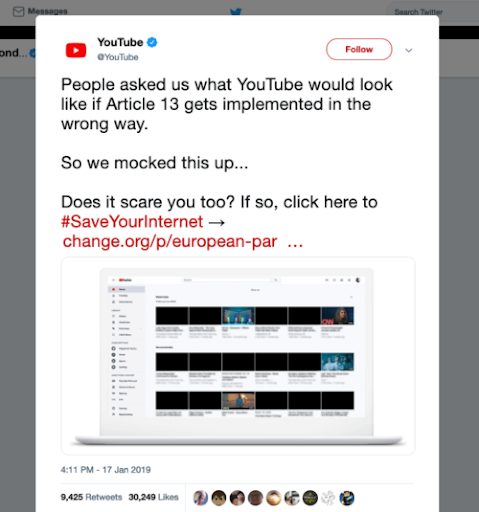

Along with this petition, potentially impacted services like YouTube have adopted campaigns using the hashtag #SaveYourInternet.

The screenshot below shows a tweet from the user-dependent media platform of a “mockup” of what might’ve happened to YouTube if draft Article 13 passed.

The YouTube CEO at the time, Susan Wojcicki, wrote on the YouTube Creator Blog, “This legislation poses a threat to both your livelihood and your ability to share your voice with the world.”

Wojcicki continued, “… if implemented as proposed, Article 13 threatens hundreds of thousands of jobs, European creators, businesses, artists and everyone they employ.”

YouTube was possibly one of the most vocal opponents to Article 13 at the time, but there were also plenty of voices outside the entertainment sector with strong opinions.

Former Parliament member Felix Reda said of the draft Directive, “The European Parliament is putting corporate profits over freedom of speech and abandoning long-standing principles that made the internet what it is today.”

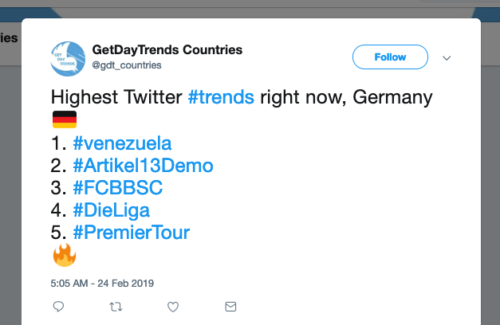

Additionally, a demonstration protesting draft Article 13 arranged in Cologne resulted in an X trend throughout Germany, as shown in the post below.

In a humorous twist, some users created memes about the possible ban on memes, like the hand-drawn version of a popular Drake meme pictured below, originally posted on Reddit by user Yamezj.

To this day, even with the meme ban never occurring, a quick internet search for Article 13 yields several negative responses and old content from 2019.

It makes for an interesting time capsule highlighting how important the Internet truly is for all of us in our modern, digital world.

When Did the Copyright Directive Take Effect?

The Copyright Directive officially took effect on June 7, 2019, and the Member States had until June 7, 2021, to establish laws supporting the directive.

However, the controversial draft of the directive was finalized on February 13, 2019.

It was then revised after trilogue negotiations on March 26 that same year and was voted on and passed a month later.

Summary

When the Copyright Directive was officially adopted, the new draft reflected the changes and concerns expressed by the general public.

Article 13 no longer exists — in its current form as Article 17, it’s much less contentious and makes exceptions for users to post content like memes, parodies, criticisms, and reviews.

But technology is adapting rapidly, and Europe has already passed other regulations that impact the digital space.

The future of the Internet is still wholly unknown — but at least for now, we can still share hilarious memes.